The month of February has been designated American Heart Month – a time to advocate for cardiovascular health and to raise awareness about lifestyle factors that affect heart disease risk. Some such factors include diet, exercise, stress management, smoking, and alcohol consumption. To support American Heart Month, February’s Fueling Facts examines dietary fat, a component that contributes to heart disease risk.

While a key ingredient in cooking, dietary fat is also an important factor in heart health. Fat provides energy, produces vital hormones, helps the body absorb fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K), and even makes up our cell membranes. While fat is essential for human functioning, it is important to understand how to incorporate fats as a healthful nutrient in your diet. While fats are the most calorically dense macronutrient, it is necessary to consider both their types and amounts to keep your plate balanced and your disease risk low. Eating too much fat or disproportionally eating less desirable types of fat can raise unhealthy LDL cholesterol and increase risk of cardiovascular disease.1 In the world of cooking, fat is used to absorb and preserve flavor, transfer heat effectively, and create appetizing mouthfeel. In this month’s Fueling Facts, our registered dietitians breakdown the three primary types of fats and examine the nutritional value and smoke point of common cooking fats.

Understanding Fats & Oils

Not all dietary fats are created equal, but they do share a similar chemical structure: a chain of carbon and hydrogen atoms. Fat molecules differ in length, shape, and number of hydrogen atoms. While these molecular differences may seem small (quite literally), they have a profound effect on the form and function of dietary fats.2 There are two primary types of fat: saturated and unsaturated. Most foods include both types, but in varying ratios.

Saturated Fat

The structure of saturated fat is comprised of a straight carbon chain with no double bonds, making it easier for chains to stack together and create a solid form. Animal products, including meat, lard, and dairy are the most common sources of saturated fat. Coconut oil and palm kernel oil are also high on the list. Saturated fat contributes to the elevation of both bad LDL cholesterol and good HDL cholesterol.3 Since elevated LDL cholesterol is linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease,4 cardiovascular death5, and potentially Alzheimer’s disease,6 it is recommended that only 5-6% of daily calories come from saturated fat.7

Unsaturated Fat

The molecular structure of unsaturated fatty acids contains one or more double bonds, making it difficult for chains to stack, thus allowing these fats to be liquid at room temperature. These fats come primarily from vegetables, nuts, seeds, and fish. They positively affect blood cholesterol and heart health when eaten in moderation. There are two broad categories of unsaturated fats: monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats.

Monounsaturated fats (MUFAs) contain fat molecules with one double bond and are most prominent in nuts, olive oil, avocado oil, and canola oil. MUFAs are the most abundant type of unsaturated fat and have been studied robustly for decades. The 1960s Seven Countries Study,9 as well as many subsequent studies, shows that replacing saturated fats with monounsaturated fats lowers bad LDL cholesterol, therefore reducing cardiovascular disease risk.10

Polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) contain fat molecules with two or more double bonds and are used to build cell membranes and nerve sheaths in the body. PUFAs are also involved in blood clotting, muscle contraction, and inflammation reduction. The two types of polyunsaturated fats are Omega-6 fatty acids and Omega-3 fatty acids, named for the location of their double bonds. Sources of Omega-6 fatty acids include safflower, soybean, walnut, and corn oils. Omega-3 fatty acids can be found in fish, chia seeds, flax seeds, and walnuts. The three main types of Omega-3s are alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Omega-3 fatty acids have powerful anti-inflammatory properties and are correlated with decreased stroke risk and increased cognitive function.11

Choosing Fats & Oils

Cooking Fat & Nutritional Value

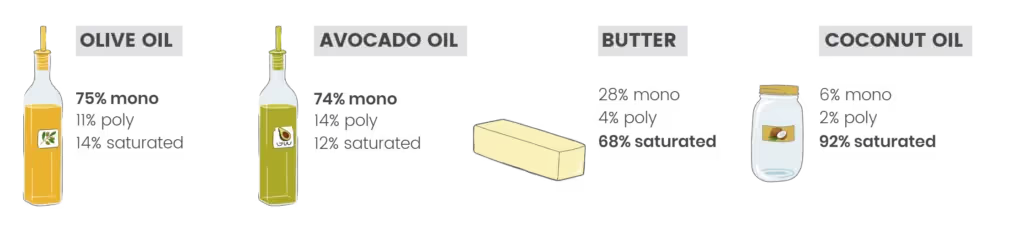

All types of fats are used in cooking. Four common cooking fats for home cooks are olive oil, avocado oil, coconut oil, and butter. The first factor to consider when choosing a cooking fat is nutritional value, specifically fatty acid makeup. As seen below, olive oil and avocado oil are predominantly monounsaturated, meaning they supply LDL-lowering benefits. Coconut oil and butter, on the other hand, are predominantly saturated. Recent studies show excessive intake of these two sources, specifically, contribute to elevated LDL cholesterol and cardiovascular risk.12,13

Cooking Fat & Smoke Point

Another factor to consider when choosing a cooking fat is smoke point. Smoke point refers to the temperature at which fat begins to break down, release harmful free radicals, and create smoke. Smoke point differs based on fat composition, origin, and refinement. Refinement involves filtration and bleaching processes to remove undesirable phospholipids, colors, and odors from oils, leaving behind a purer product.15 Refined oils have higher smoke points than animal fats or “virgin” oils. Butter, for example, contains milk solids, making it more susceptible to burning, so olive and avocado oils are best for cooking at higher temperatures.16

Using Fats & Oils

Dietary fats and oils are essential nutrients, but when consumed excessively or used incorrectly, they pose a risk to cardiovascular health. Consider the recommendations below to optimize the benefits of healthy fats:

- Choose olive oil, avocado oil, or another monounsaturated-dominant plant oil mostly when cooking and preparing food.

- Use an oil with a higher smoke point, such as avocado oil, for grilling, stir-frying, or baking at temperatures above 400◦

- Enjoy saturated fats, such as butter or coconut oil, moderately. Keep overall calories from saturated fats to less than 6% of daily calories (for a diet of 2,000 calories, which equates to no more than 13 grams of saturated fat per day).

If you have questions about how to incorporate dietary fats into your diet in a healthy way, reach out to your SHIFT Registered Dietitian for more individualized recommendations.

In Real Health,

Rachel & Lauren

SHIFT Registered Dietitians

References

- Harvard Health Publishing. The truth about fats: the good, the bad, and the in-between. Harvard Health. Published December 11, 2019. https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/the-truth-about-fats-bad-and-good

- Ibid.

- Mayo Clinic. Learn the facts about fats. Mayo Clinic. Published 2019. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/fat/art-20045550

- Mayo Clinic. Learn the facts about fats. Mayo Clinic. Published 2019. https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/fat/art-20045550

- Jung E, Kong SY, Ro YS, Ryu HH, Shin SD. Serum Cholesterol Levels and Risk of Cardiovascular Death: A Systematic Review and a Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8272. Published 2022 Jul 6. doi:10.3390/ijerph19148272

- Zhou Z, Liang Y, Zhang X, et al. Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:5. Published 2020 Jan 30. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2020.00005

- American Heart Association. Saturated Fat. www.heart.org. Published November 1, 2021. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/fats/saturated-fats

- White B. Dietary Fatty Acids. American Family Physician. 2009;80(4):345-350. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2009/0815/p345.html

- SCS. Mediterranean style diets and cardiovascular disease. Seven Countries Study | The first study to relate diet with cardiovascular disease. Published October 20, 2012. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://www.sevencountriesstudy.com/mediterranean-style-diets-and-cardiovascular-disease/

- Grundy SM. Monounsaturated fatty acids and cholesterol metabolism: implications for dietary recommendations. J Nutr. 1989;119(4):529-533. doi:10.1093/jn/119.4.529

- Chen C, Huang H, Dai QQ, et al. Fish consumption, long-chain omega-3 fatty acids intake and risk of stroke: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2021;30(1):140-152. doi:10.6133/apjcn.202103_30(1).0017

- Neelakantan N, Seah JYH, van Dam RM. The Effect of Coconut Oil Consumption on Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Circulation. 2020;141(10):803-814. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.043052

- Jayawardena R, Swarnamali H, Lanerolle P, Ranasinghe P. Effect of coconut oil on cardio-metabolic risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(6):2007-2020. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2020.09.033

- Feingold KR. The Effect of Diet on Cardiovascular Disease and Lipid and Lipoprotein Levels. [Updated 2021 Apr 16]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570127/

- Gharby S. Refining Vegetable Oils: Chemical and Physical Refining. ScientificWorldJournal. 2022;2022:6627013. Published 2022 Jan 11. doi:10.1155/2022/6627013

- Moncel B. Smoking Points of Cooking Fats and Oils. The Spruce Eats. Published August 20, 2011. https://www.thespruceeats.com/smoking-points-of-fats-and-oils-1328753

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

%201.webp)